Written By: Juliet Crosby, Principal Consultant – Energy Transition

Rapid Changes Create a Perfect Storm

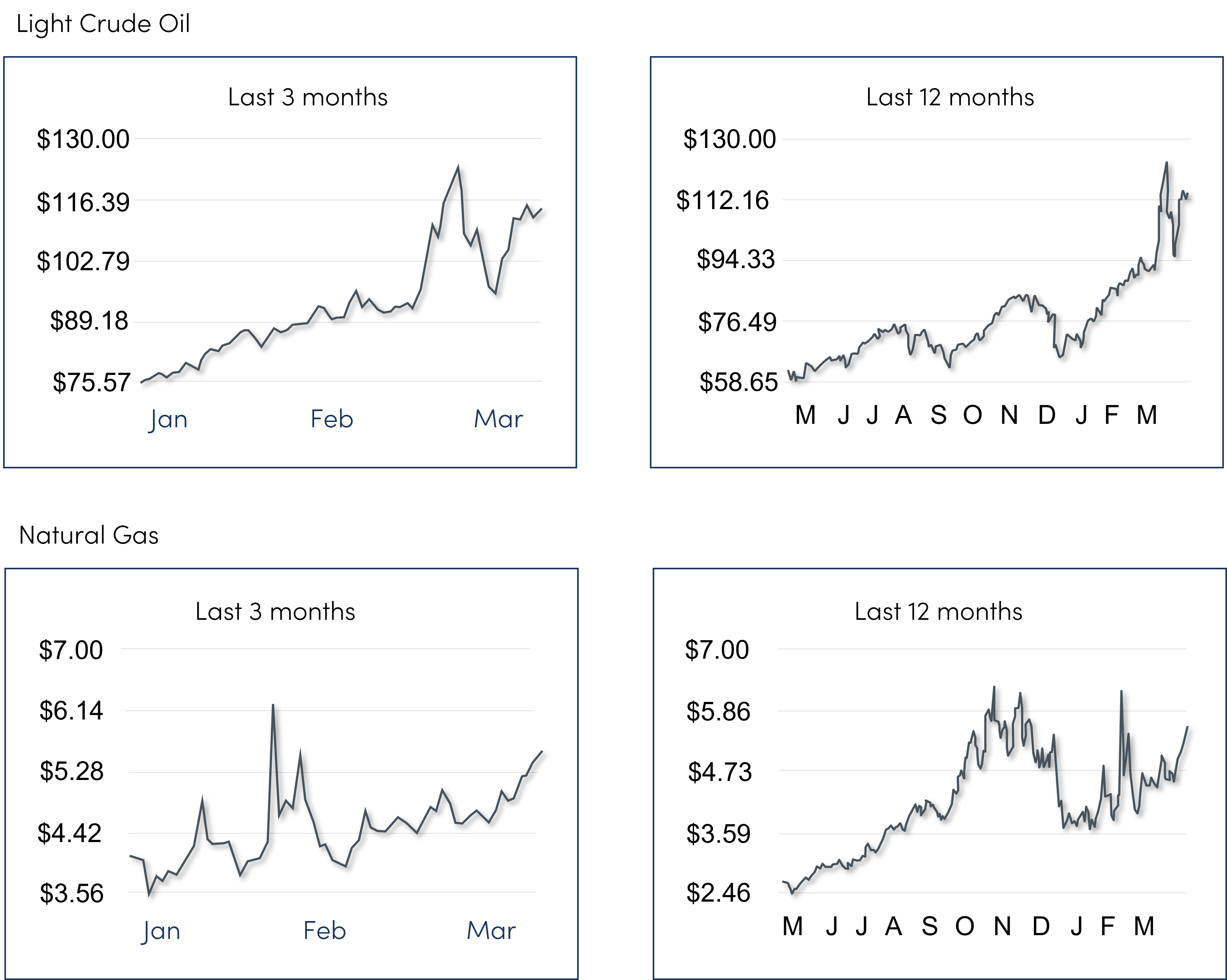

With the outbreak of war in Europe, the human cost of which is all too obvious, already climbing energy prices have inevitably risen even more sharply. Sadly, there is no sign the conflict will de-escalate quickly and wide-reaching sanctions have the potential to become long-term. Governments are scrambling to enact policy changes to address energy supply, security, and cost, creating questions as to whether the energy transition and aspirations to net-zero will speed up or stall as a result. Similarly, companies globally have complex new strategic questions to answer and risks to manage. Prior to the invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, energy prices were rising due to a combination of factors, including a more rapid than expected economic recovery from the plunge in energy consumption experienced at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Additionally, oil and gas supply has increased slowly following years of reduced investment as companies strived to live within cash flow and investors fled the sector.

From: Oil Prices and Gas Prices with Graphs, Charts, Trends, and News | RIGZONE Note: gas prices show a different trend to oil prices due to advance contracts, but gas futures have risen sharply.

We’re Already Seeing Warning Signs

Taking the UK as an example, there are already signs of shortages of diesel and heating oil, with garage forecourts running dry and heating oil deliveries unavailable. This contributed to rumours that the UK government were considering issuing new North Sea oil and gas licenses, potentially at odds with the UK government’s commitment to reach net-zero by 2050. Other governments and organisations, including the US and the EU giving similar indications of softening their positions on previously stated aspirations to decrease the production of, and end exploration for, hydrocarbons.

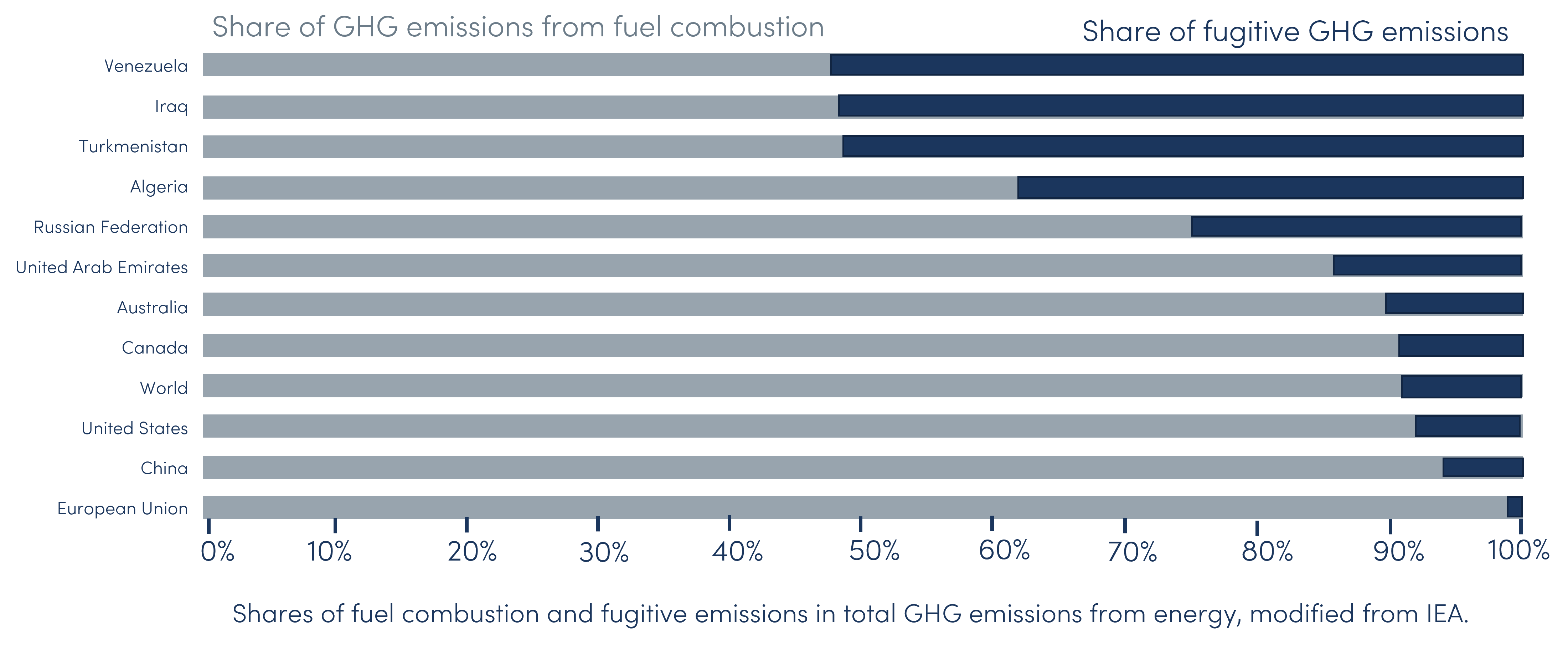

It could be argued that Greenhouse Gas (GHG) reductions may stall as countries with capacity boost domestic production in an attempt to secure energy supply and mitigate increasing costs. However, raising domestic oil and gas production where possible may actually lower carbon intensity compared with importing oil and gas. For instance, the IEA chart below shows how fugitive methane emissions vary by area), with the EU and UK demonstrating the fewest fugitive emissions. Conversely, oil-exporting countries such as Venezuela, Iraq, and Russia have higher fugitive emissions, and oil and LNG produced in these countries must be shipped to end markets, with shipping resulting in more emissions.

A Silver Lining

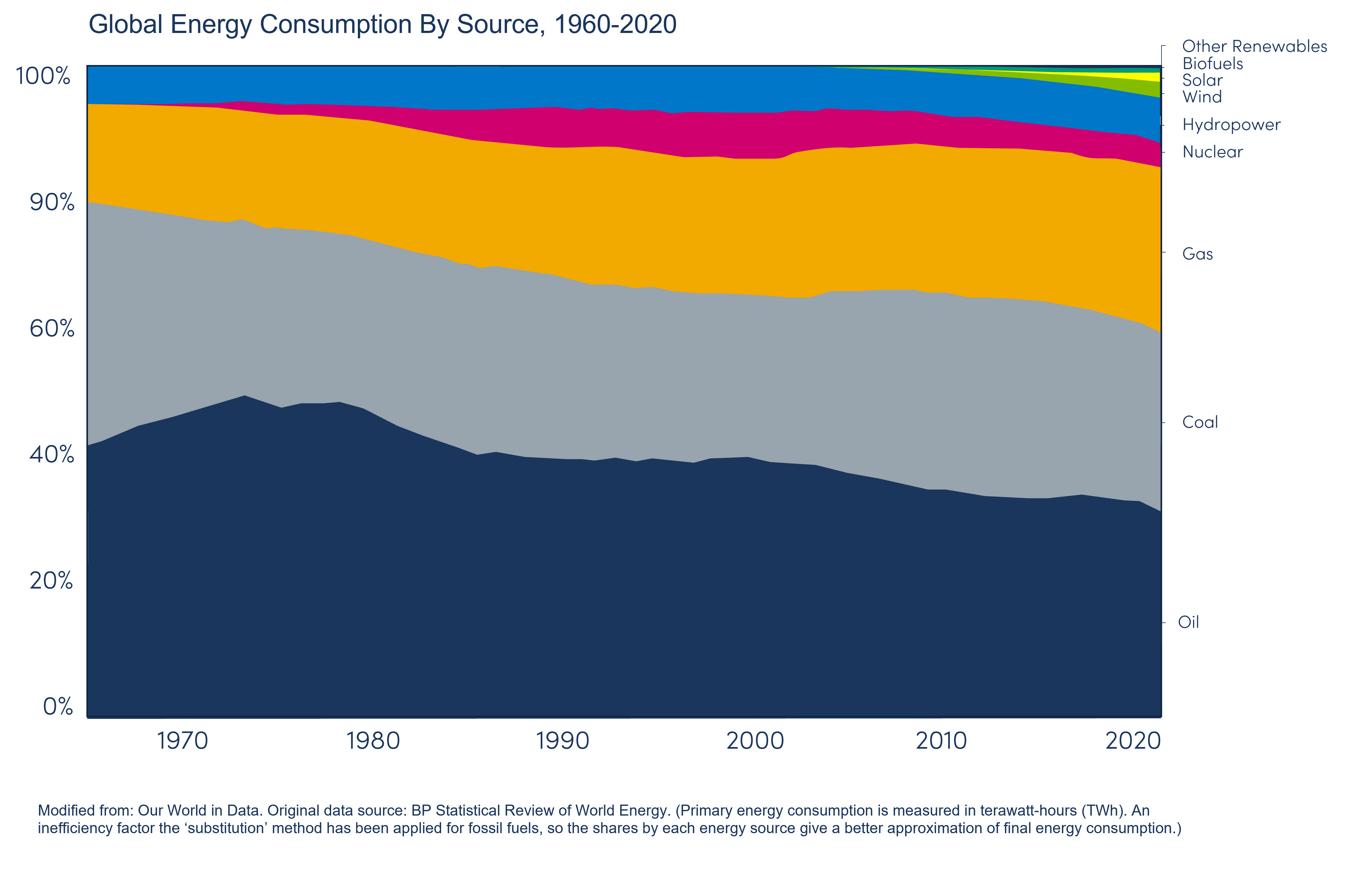

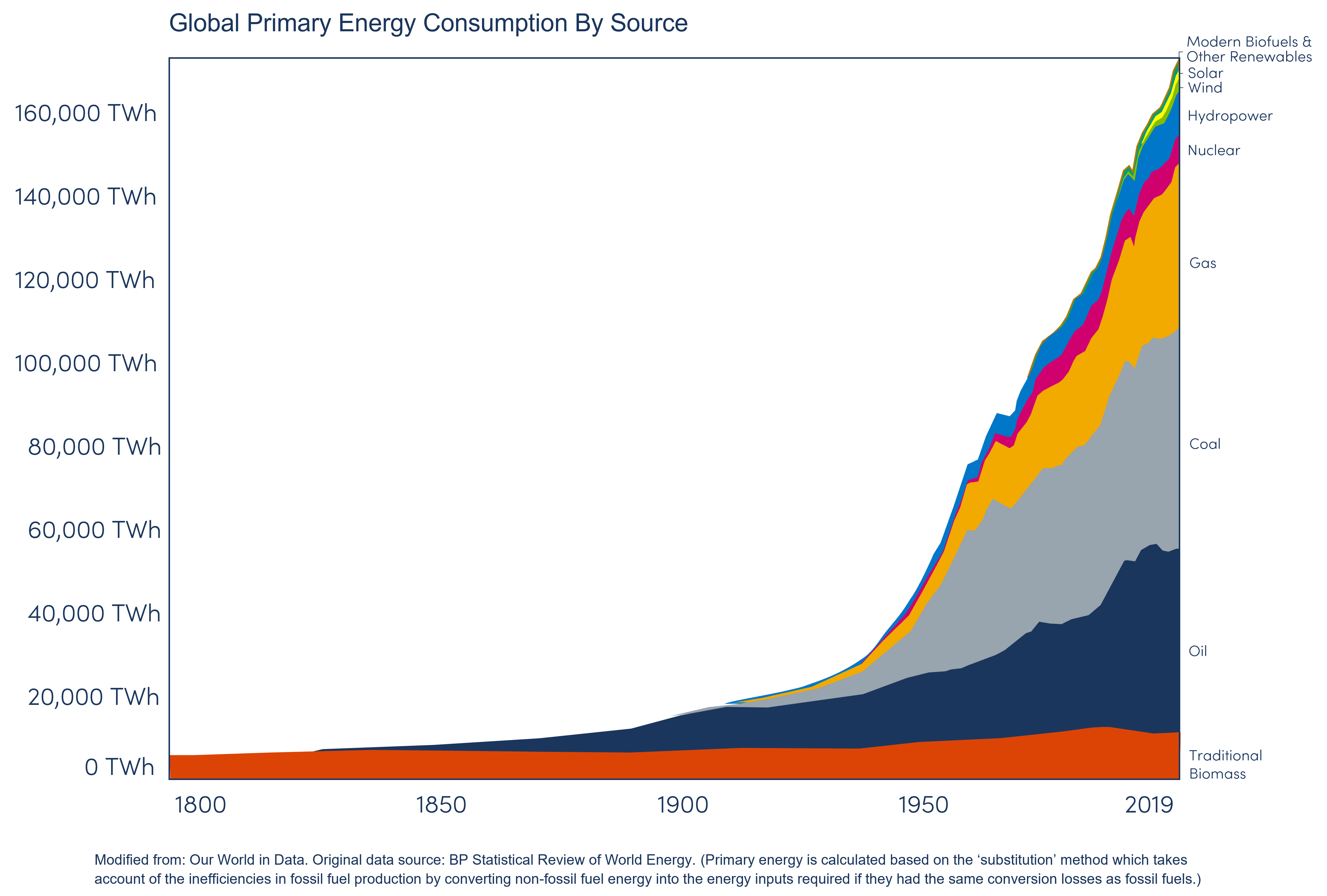

Interestingly, rising costs of hydrocarbons will make renewable energies more cost-competitive, allowing options such as geothermal energy, which requires high capital outlays, to become more financially viable. Continuing encouragement from governments and financial incentives, along with investor appetite for sustainable investments, have seen the enterprise values of renewable developers and suppliers increase by more than 100% in recent years. The renewable energy sector will continue to grow exponentially. However, the following charts illustrate that hydrocarbons are still the dominant energy source, and the world will need to bridge a significant energy gap to reach net zero, particularly as global energy demand continues to grow.

What Should Energy Companies Do Now?

Oil and gas companies show differing strategic responses to the Energy Transition, as illustrated by the following graphic from Carnrite Group.

It’s worth noting that even companies in the ‘double down’ categories will need to work to reduce their GHG emissions due to investor demands, stakeholder pressures, and regulatory reporting requirements, which are already in force in many areas. This is particularly true for high-carbon industries such as oil and gas. Reporting requirements and the trend for investors to demand strong Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance means that companies need to have a realistic plan for emissions reduction, along with monitoring to demonstrate progress.

While oil and gas prices remain high, it may be that more companies, particularly those who don’t have public shareholders to answer to, will double down to maximise profit from the high prices. Obviously, this is unpalatable to governments and consumers, but policies have driven a decline in oil and gas production in areas such as the UK and EU, which may make it hard to increase oil and gas production from existing fields domestically. Exploration for new fields has been even more hard-hit because of low prices and environmental concerns, so with the oil and gas conveyor belt effectively stalled and bringing new fields into production potentially taking years to achieve, it will be challenging for domestic oil and gas to bridge the current supply problems or energy transition gap even if new investment is encouraged. Besides which, companies may not be prepared to risk investment knowing that the tide could easily and quickly turn against them again.

Looking to the Future

High oil and gas prices may help to decarbonise the oil and gas industry. Companies aspire to be more sustainable, but the investment required to achieve meaningful emissions reductions would previously have rendered projects loss-making, creating a difficult balance between environmental stewardship and creating financial returns for shareholders. Hopefully, high oil and gas prices will create the cash flow needed to invest in emissions reduction projects and new, low carbon oil and gas projects that enable the EU and UK to reduce their reliance on higher emission imported oil and gas. Meanwhile, lack of affordability and tougher times for consumers (desperately so for some) are likely to drive behaviour change and reduced consumption which could also reduce carbon emissions.

Sky-rocketing energy prices have created a renewed focus on both cost and security of energy supply, simultaneously accelerating the desire for nations to invest in renewable energy and forcing governments to acknowledge that oil and gas are necessary parts of the energy mix for years to come. Oil and gas production in places like the EU, UK, and US often have lower emissions than countries on whom we rely for imported hydrocarbons, making their domestic production an attractive alternative to imports. Governments and companies have a lot to think through and we are here to help.